Ninety-nine percent of the Earth’s crust is made up of only nine elements: oxygen, silicon, aluminium, iron, calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, and titanium. The more than 80 remaining elements account for only 1%.

The places on Earth where there are mineral-rich ore deposits that are ‘economically viable’ to mine are therefore pretty important and increasingly so as countries move away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy, and increasingly advanced tech is created.

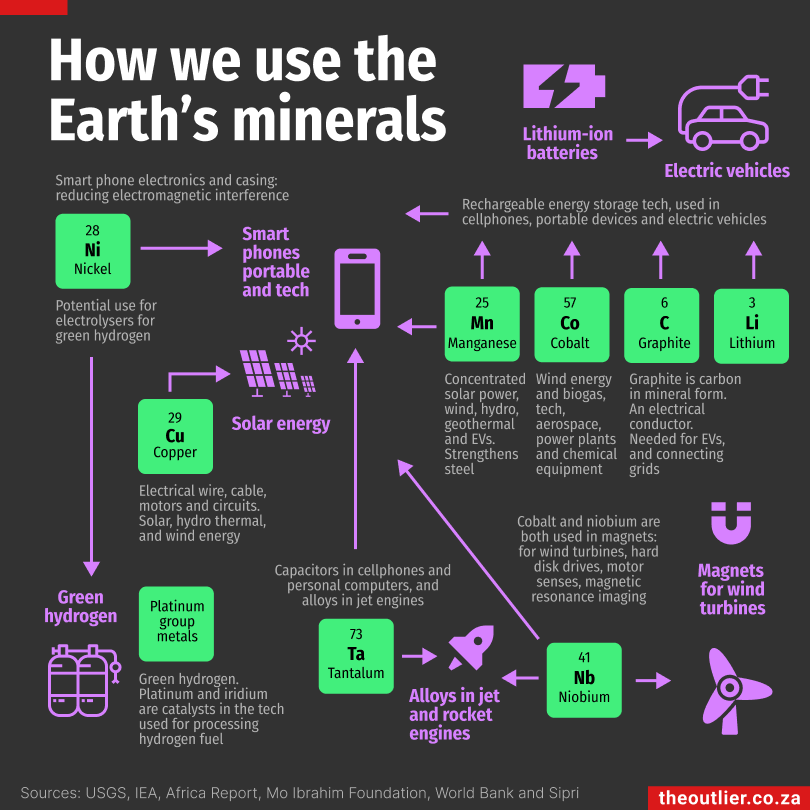

Clean energy systems require so-called critical minerals. There are five core critical minerals, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA): copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel, graphite and rare earths. But there are many others, such as arsenic, bismuth, gallium, germanium, hafnium, magnesium, manganese, niobium, platinum group metals, tantalum, tungsten and vanadium, all of which play different roles in energy tech.

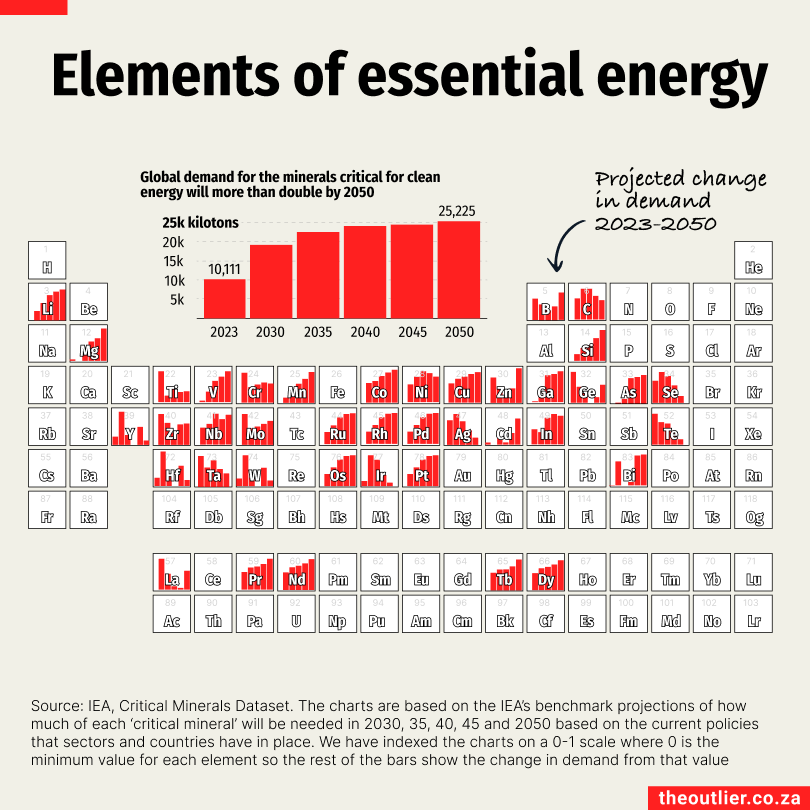

In the periodic table below, the bars in each ‘critical element’ for clean energy show the IEA’s projection of global change in mineral demand between 2023 and 2050 based on the existing climate change and other policies of countries. Demand is expected to more than double by 2050.

If countries do actually fully implement the changes needed to cut their greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, then the quantity of these minerals required would quadruple, according to the IEA’s projections.

What are they used for?

Clean energy is not the only driver of the demand for critical minerals. Tech is developing rapidly, which means the demand for the raw materials used to build this tech future will keep rising.

Take manganese, for example. It’s used in solar, wind and geothermal energy projects as well as electric vehicles. Demand is expected to increase substantially by 2050 (see Mn on the periodic table above). Incidentally, South Africa produced a third of the world’s manganese in 2023 (the latest available non-estimates data from the United States Geological Survey).

Then there’s lithium (Li), which is used in battery storage, mobile devices and electric vehicles; copper, which is used in green energy; nickel, which is used in mobile devices, and niobium, which is used in mobile devices, wind turbines and rocket engines. See the infographic below for more on the uses of critical minerals.

Where do you find them?

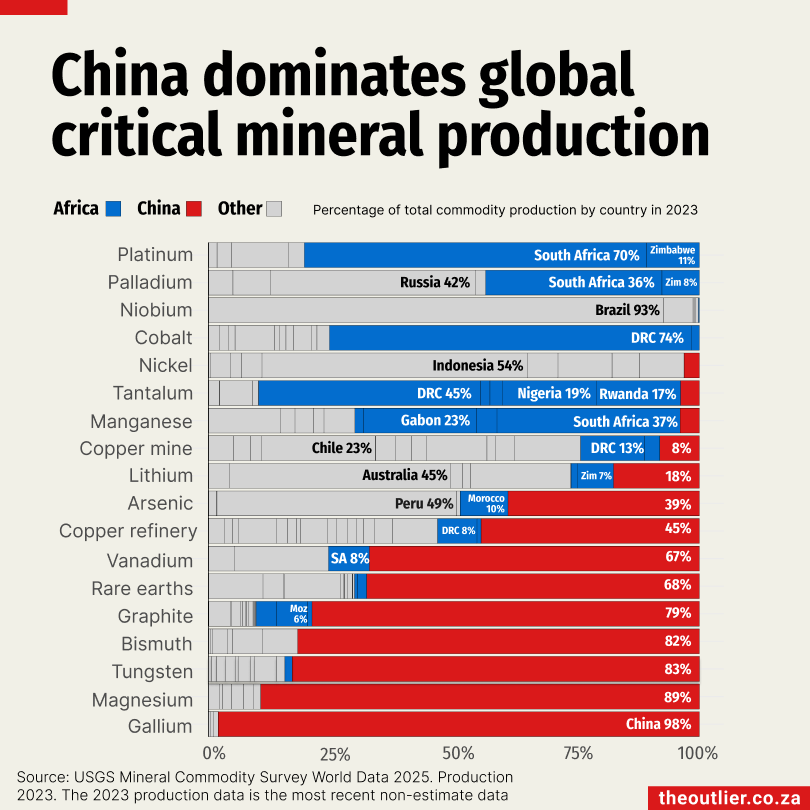

Most minerals come from China, which the United States and European Union are not happy about. The EU has committed to green energy policies and needs a way to implement them, and the US sees China’s dominance in critical mineral production as a security threat (and has a ‘national defence stockpile’ of 42 mineral commodities). They are all keen to find alternative supplies.

Where does Africa fit in to this?

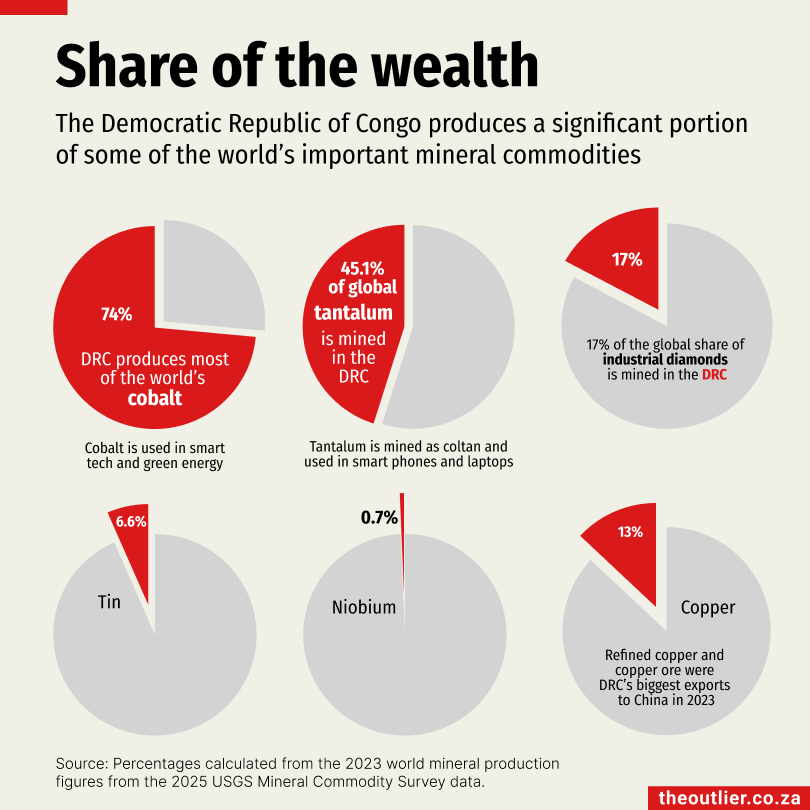

African countries are rich in reserves and potential. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) produces three-quarters of the world’s cobalt. Most of the world’s tantalum, manganese and platinum group minerals are produced in African countries.

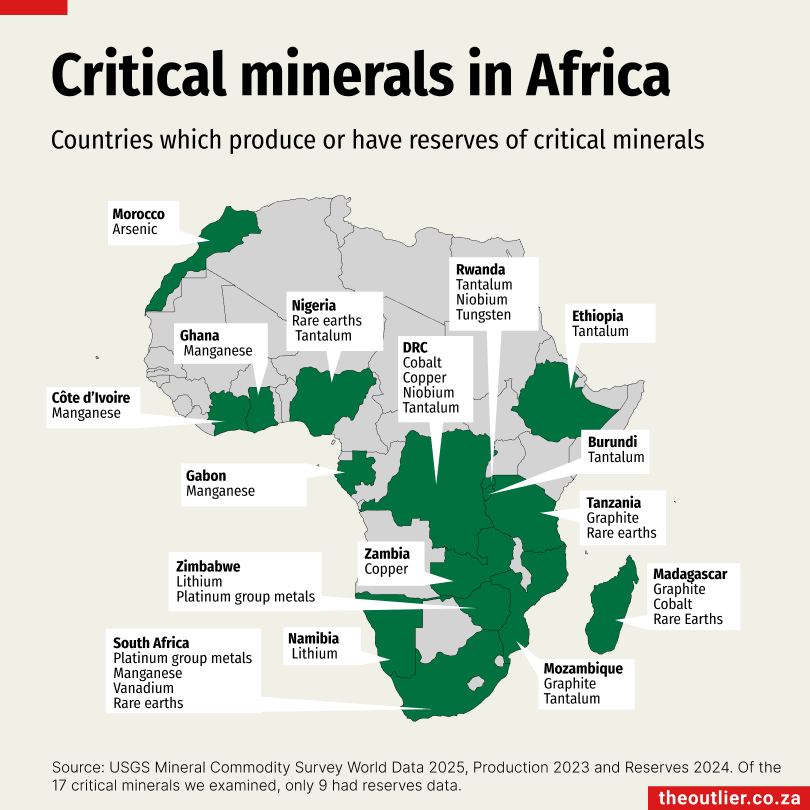

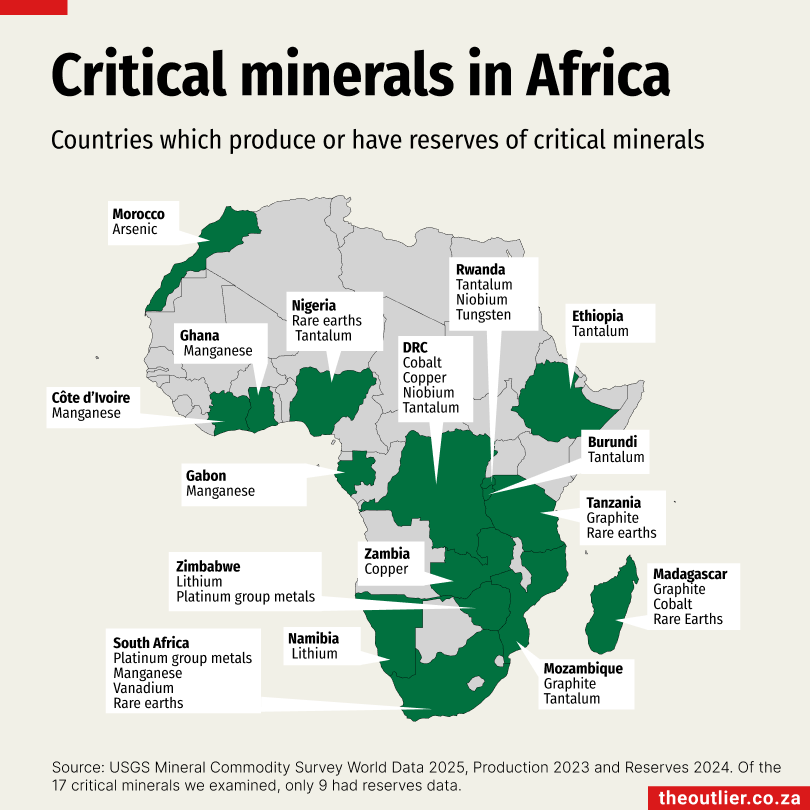

The map below shows countries that produce or have reserves of 18 critical minerals, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Mineral Commodity Survey World Data 2025. South Africa has 77.5% of the world’s platinum group metals reserves as well as 33% of manganese and 3% of vanadium.

China has strong economic ties with many of the African countries that produce the valuable mineral resources that it lacks, and even those with resources that it has. China is the DRC’s biggest mineral export partner. Accessing minerals has become a political issue for many countries. In the meantime, the USA has already developed policy and research into space mining!

It is well documented that there is a ‘resource curse’ or ‘paradox of plenty’, where countries with raw minerals often are economically underdeveloped. Mineral-rich (African) countries would greatly benefit from refining and beneficiating their own minerals, while wealthier countries prefer to buy the raw minerals.

Increasing awareness of ‘conflict minerals’ means that globally, regulations around trading have tightened significantly. However, many critical minerals have flown below the radar – where they are deeply connected to conflicts, wars, trafficking, and human rights violations but are not considered ‘conflict minerals’, and international trade around them remains under-regulated.

While millions of people living in the DRC live in extreme poverty, the country has trillions of dollars in mineral wealth under its soil. Artisanal mining (small scale, subsistence) is still predominant.

It is one of the most important countries in terms of critical minerals, particularly because of its cobalt and coltan. ‘Coltan’ is the term used to describe columbite-tantalite (which contains tantalum and niobium). Small amounts of tantalum powder are used to make the heat-resistant capacitators in almost all smart technology that we use, like our cell phones and laptops.

The DRC has been producing up to 70% of the world’s cobalt, which is used in lithium-ion batteries, although China refines most of it.

Much of the conflict in the DRC relates to control and movement of these resources. A range of actors are reported to be involved in these mineral supply chain conflicts, including the government and army of the DRC and its neighbouring countries as well as foreign states with mining interests in the country.