On 10 July, Judge Mmonoa Teffo handed down judgment of the inquest into the deaths of 141 of the 144 mental health patients of the state who died in 2016 and 2017 when they were moved from Life Esidimeni facilities.

She found that former Gauteng Health MEC Qedani Mahlangu and the former head of mental health in the Gauteng health department, Makgabo Manamela, can be held responsible for deaths of at least nine Life Esidimeni patients. The National Prosecuting Authority will now need to decide if it will proceed with criminally prosecuting Mahlangu and Manamela.

How it happened

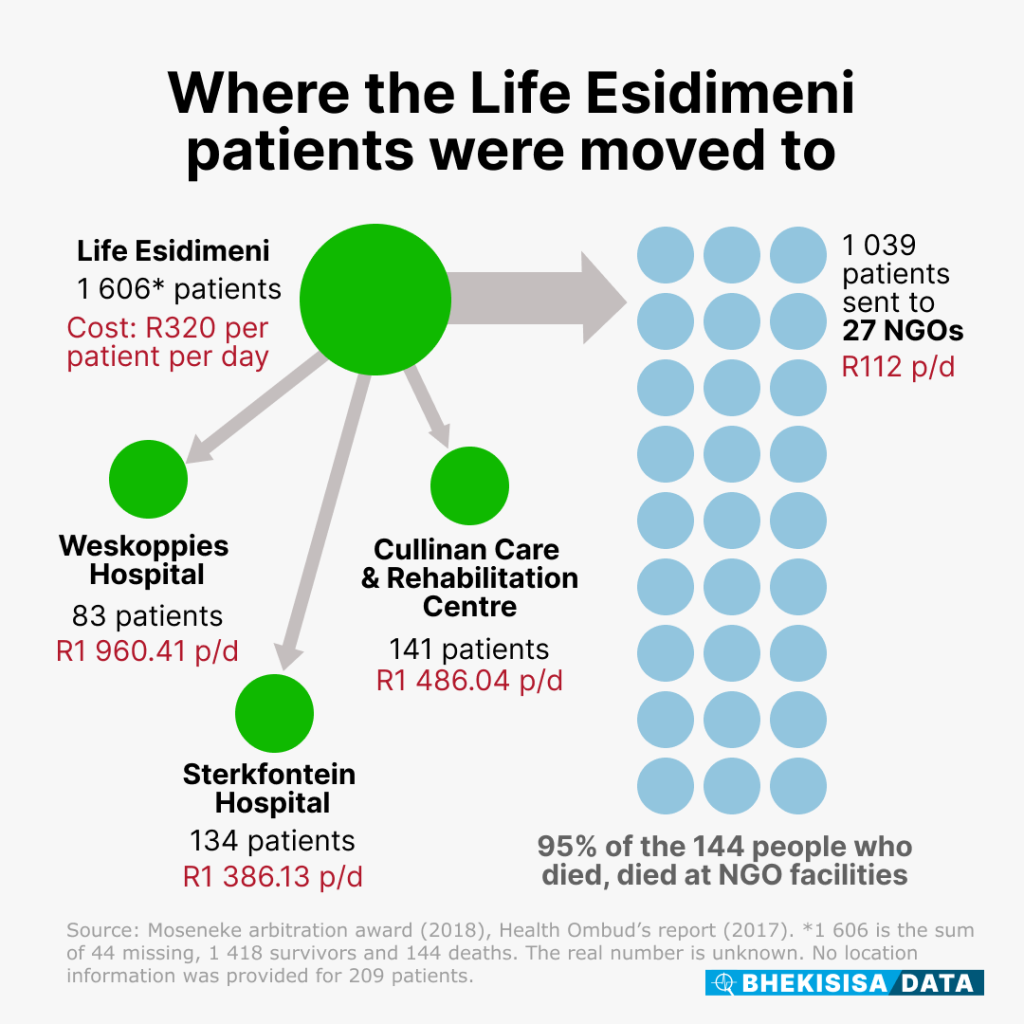

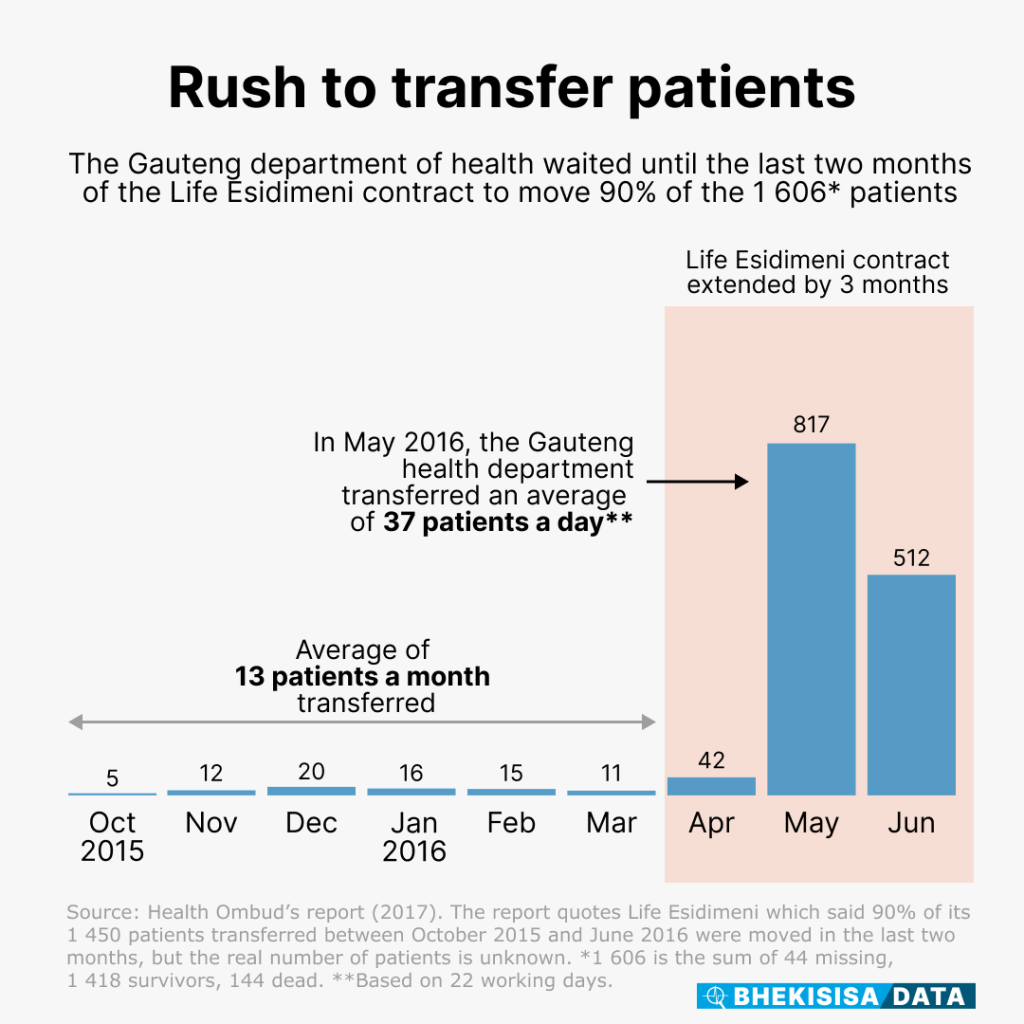

In September 2015, the Gauteng department of health decided to end a contract with Life Esidimeni, a group of specialised private psychiatric care hospitals. The decision was part of a wider plan to deinstitutionalise mental healthcare users in the province by placing them into non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in communities. It was also to cut costs.

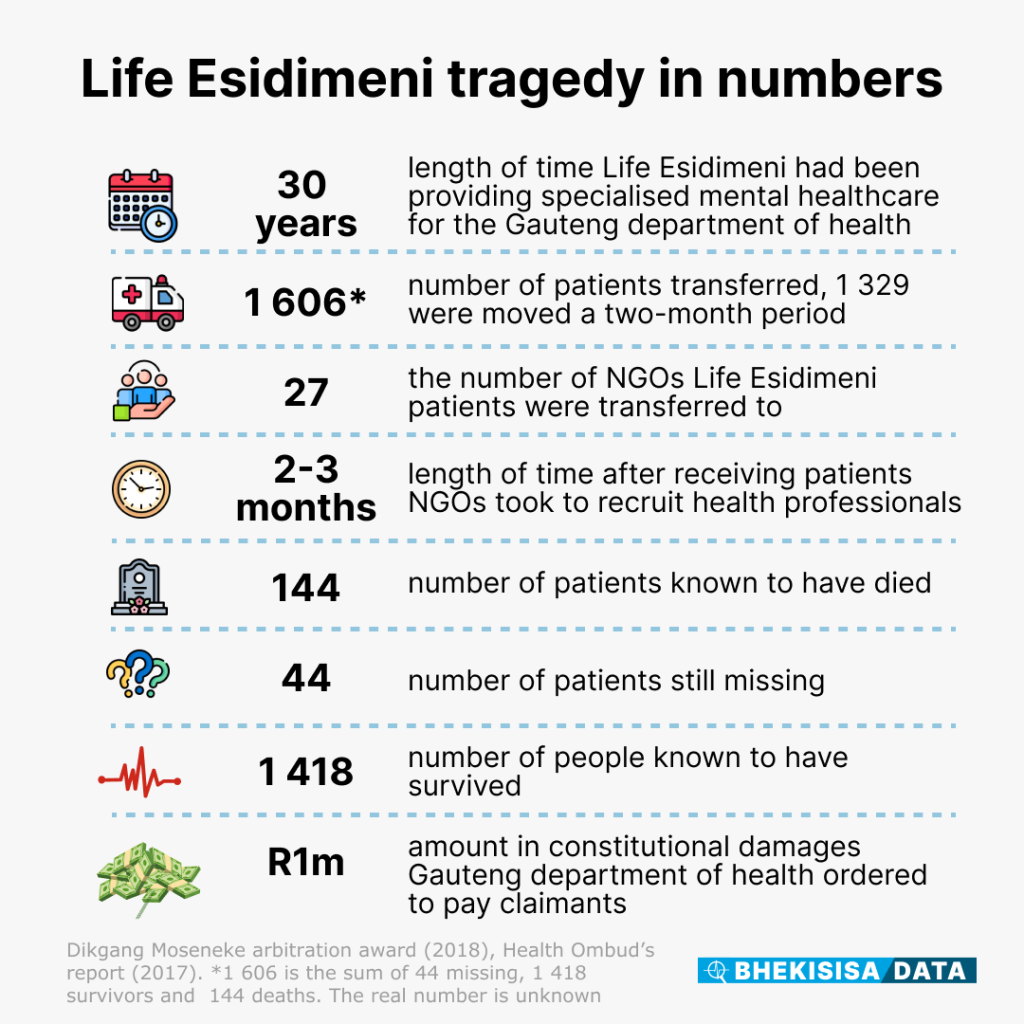

What transpired was a poorly planned, hastily executed tragedy that led to at least 144 people dying and 44 going missing.

By 2024, no one had been charged for what happened to the more than 1,600 people with serious mental health conditions after they were transferred from Life Esidimeni’s facilities to 27 non-profit organisations, most between May and June 2016.

Three high-ranking Gauteng health officials resigned from their posts as a result of their involvement in the Life Esidimeni tragedy between 2017 and 2018:

- Gauteng MEC for health Qedani Mahlangu, who, according to Section27, made the decision to transfer the patients from Life Esidimeni

- Barney Selebano, head of the Gauteng provincial government’s health department

- Makgabo Manamela, the department’s director of mental health, who, according to Section27, was responsible for implementing the transfers

Looking for justice

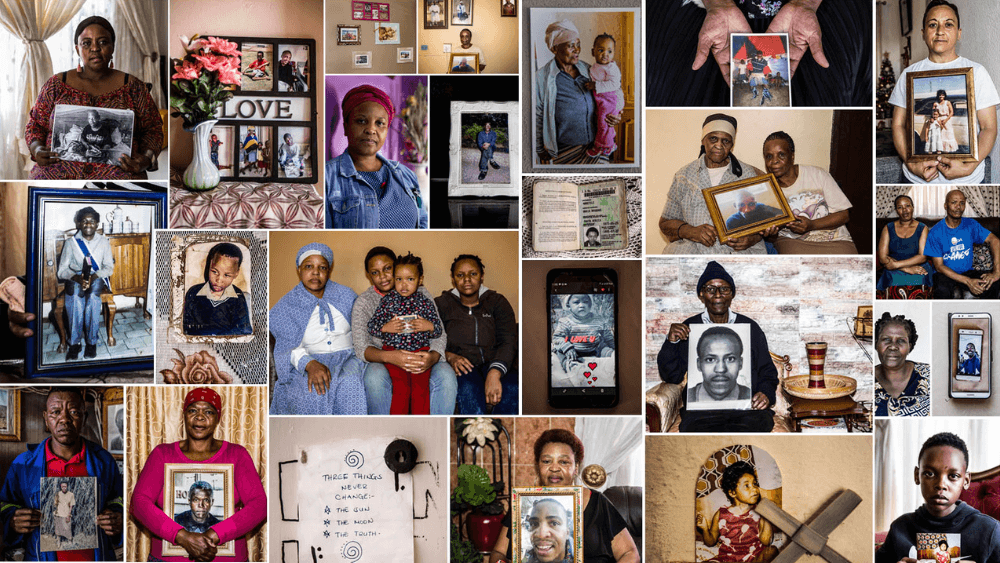

In August 2016, Christine Nxumalo went looking for her sister, Virginia Machpelah, and discovered that she and eight other former Life Esidimeni patients had died at Precious Angels, a community facility, not long after they had been moved there.

In September, the health minister called for an inquiry by the health ombud, Malegapuru Makgoba. By October, Makgoba had called for Life Esidimeni patients sent to the Cullinan Care and Rehabilitation Centre (CCRC)/Anchor complex to be helped urgently, writing that ‘relatives of patients are complaining about the poor quality of care of loved ones in terms of nutrition and medication. Some patients are simply wasting away and some are reported to be staring death in the eye in front of relatives.’

The Cullinan Care and Rehabilitation Centre is a public psychiatric hospital. Two NGOs, Anchor and Siyabadinga, were housed in unused wards of the hospital, according to Sasha Stevenson, executive director of Section27, the human rights organisation that represented victims and their families in the later inquest into how the transfers unfolded.

The ombud found that the non-profit facilities were not well prepared for receiving patients and didn’t have the right staff, proper infrastructure and funding to care for patients.

‘Mental healthcare users were tortured, abused, punished and in some cases deprived of food, water and adequate shelter and sanitation at the (often overcrowded) unlicensed NGOs,’ notes Section27 on their website. Patients were not given the medication or treatment they needed and many became dehydrated, developed secondary infections such as pneumonia or had uncontrolled seizures.

‘Chaotic’ implementation

At the time of the health ombud’s report, 75 of the (then 94 known) deaths occurred at five of the nonprofits:

- CCRC/Siyabadinga/Anchor 25

- Precious Angels 20

- Mosego/Takalani 15

- Tshepong 10

- Hephzibah 5

The health ombud’s report noted that the ‘rushed implementation’ was ‘chaotic’. A policy change of this size could have taken ‘up to five years’, but instead was executed over nine months, rapidly scaling up in the last three months, it said.

The move, touted as a cost-saving measure, allocated only R112 per day per patient at the 27 NGOs, compared with the R320 Life Esidimeni facilities could spend on each patient a day. Some of the organisations received funding from the provincial health department only three to four months after Life Esidimeni patients arrived.

Hope for healing

On 9 October 2017, arbitration hearings started before former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke, who had to decide what would be fair compensation for victims of the transfer project. Over the next 45 days (until 9 February 2018), 60 witnesses testified, including 12 government officials.

By this time, the known death toll was 144 people and 44 were missing; 1,418 of the transferred patients survived, Moseneke’s report said.

Moseneke ordered the Gauteng health department to pay the victims and their families who participated in the arbitration, R1-million in constitutional damages plus other costs (some received a total payout of R1.2-million) as restitution for their treatment during the transfers.

Notebook

- This story was produced by Bhekisisa and Media Hack. It was first published by Bhekisisa. Read it here

- Useful links and more stories in Bhekisisa’s Life Esidimeni special feature

- Section27