📝 By Gemma Ritchie and Laura Grant

South Africa needs a rapid switch to renewable energy. Not only is it critical to keep global temperature increase and its consequences in check, it would also be good for South Africa’s economy. This was a key message of a public lecture at Wits University this week by Sir David King, the head of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group and the former chief scientific advisor to the UK government.

King, who studied at Wits in the 1960s, urged South Africa to lead the global south in the transition away from fossil fuels in an inspiring talk entitled ‘The Paris Agreement at a Crossroad: Pathways to a Sustainable Future’.

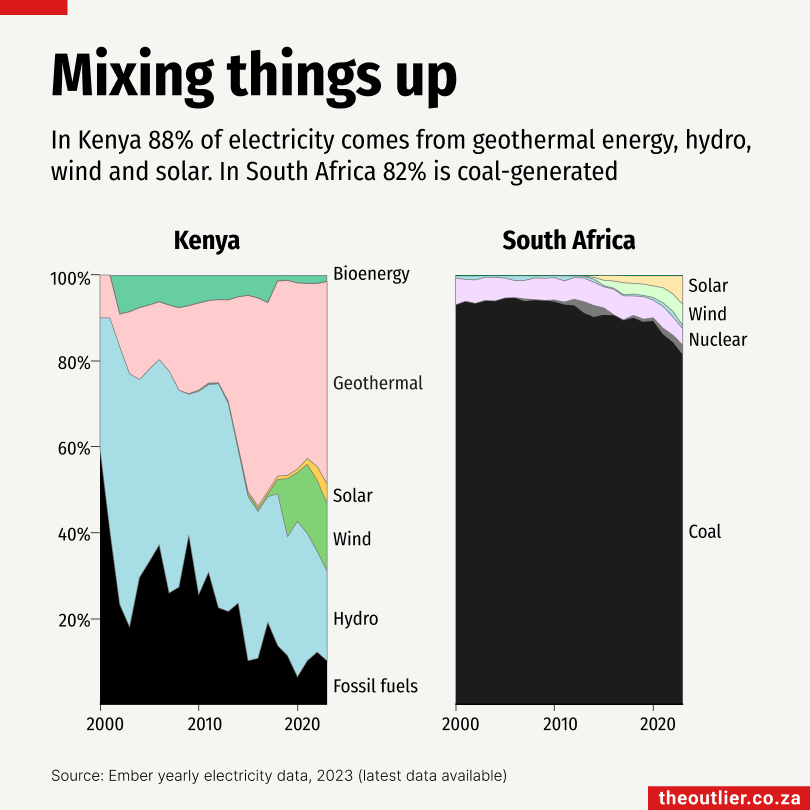

He held up Kenya, which generates nearly 90% of its electricity from non-fossil sources, as an example of what’s possible in Africa. South Africa is still heavily dependent on coal, but renewable energy’s share of the mix is increasing.

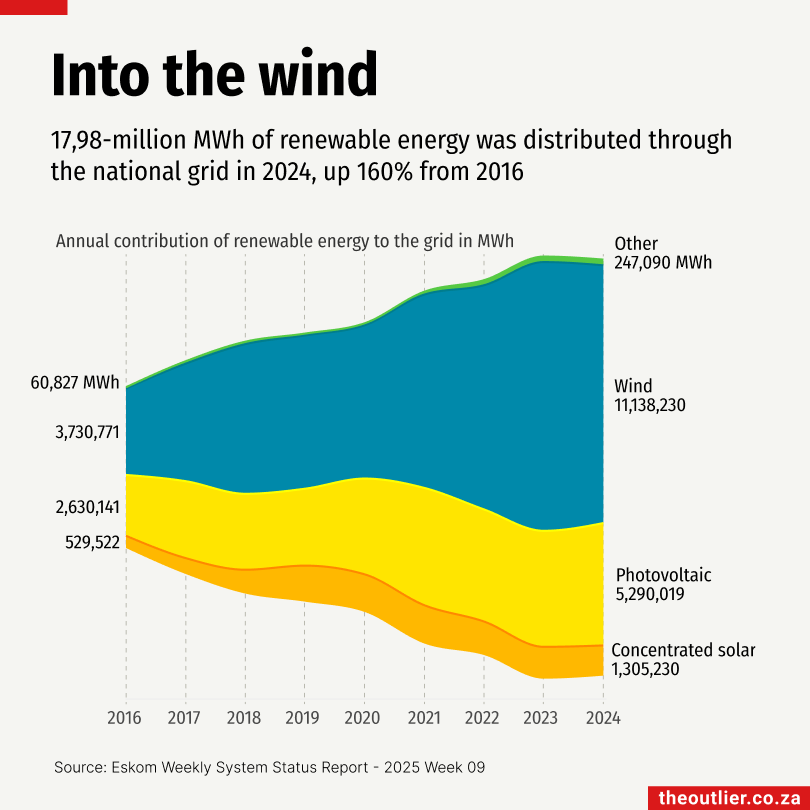

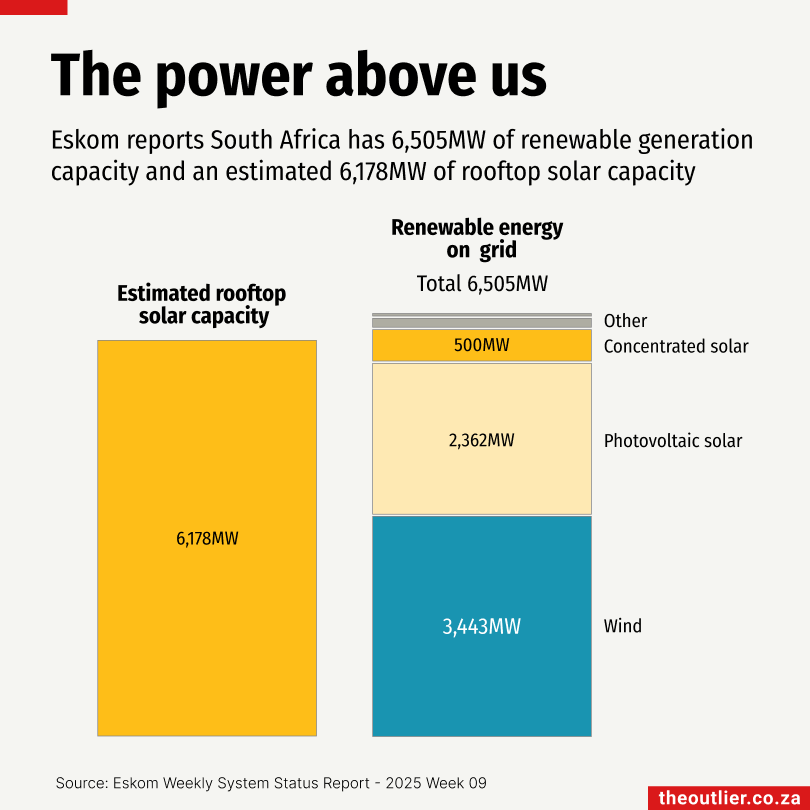

South Africa has 6,505MW of installed renewable energy capacity that generates power for the national electricity grid, according to Eskom. 53% is wind and 44% is solar. Just under 18-million megawatt-hours of electricity from renewables was generated in 2024, nearly two-thirds of it wind, the utility reports. One megawatt hour of electricity can power between 500 and 1,000 homes for an hour. There’s a long way to go before renewables can replace coal. But it’s a start.

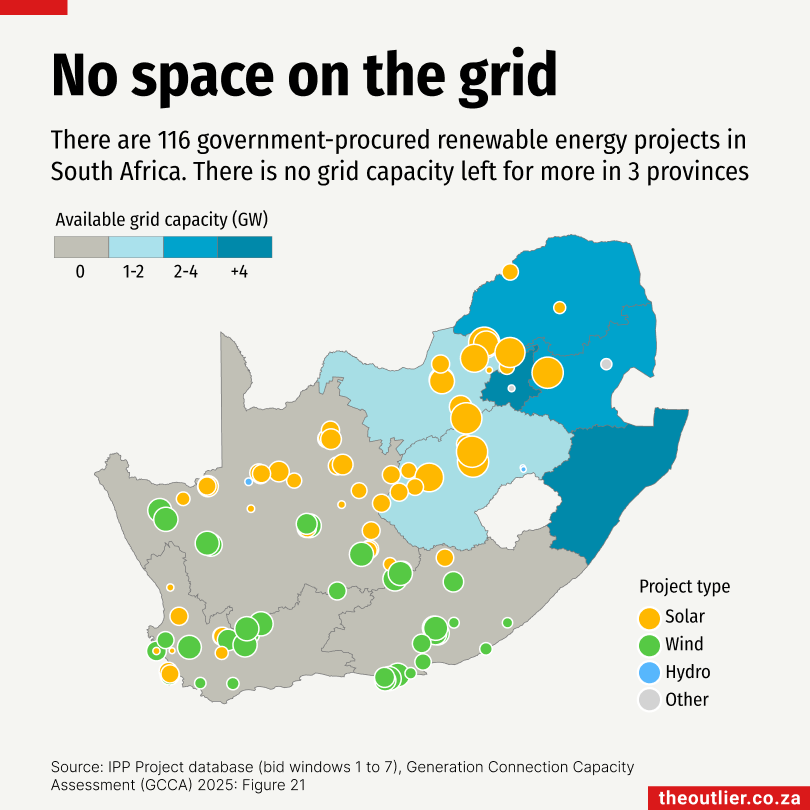

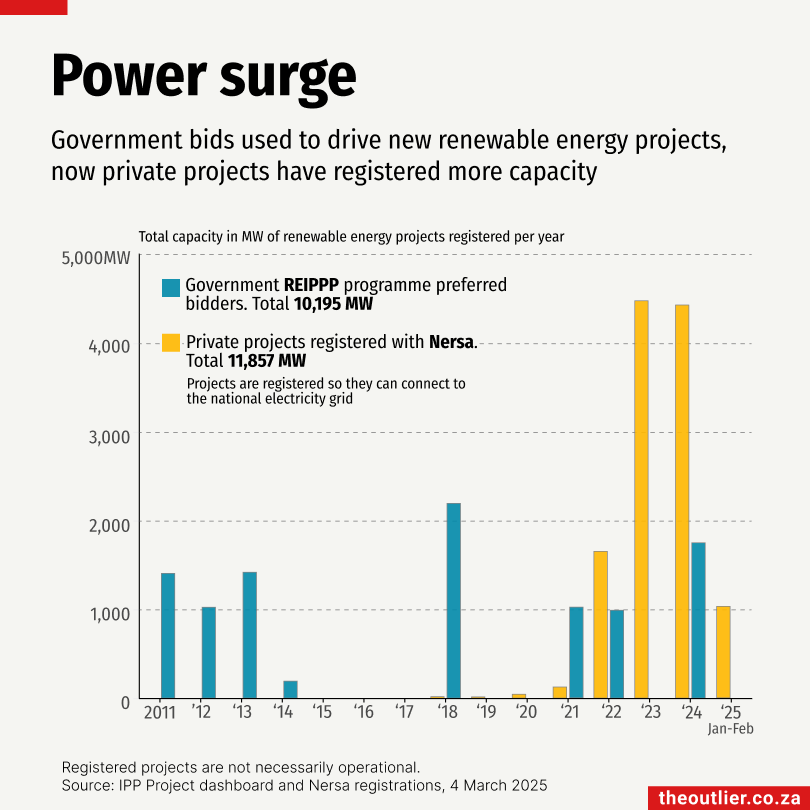

A key driver of the increase in renewable capacity is the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). Launched in 2011, it was designed to facilitate private sector investment in renewable energy projects that connect to the national grid through a competitive tender process. Since its inception, 116 projects have been approved, in seven bid windows. Ninety-one of these projects are operational.

Forty REIPPPP projects are wind farms. Although there are more solar projects than wind projects, at present the wind farms are generating more electricity for the grid.

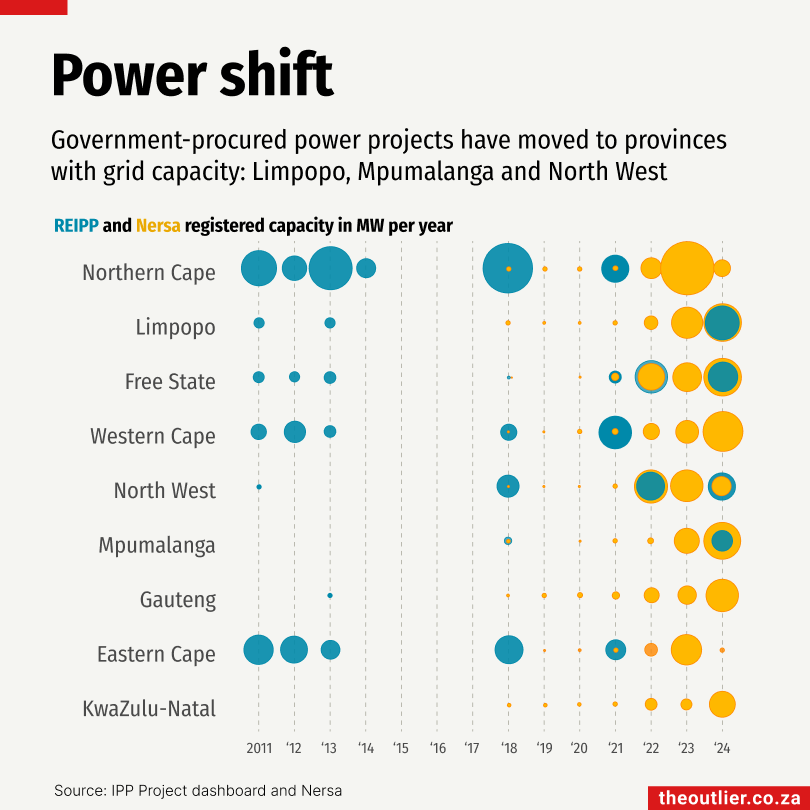

But there’s a problem. The areas that are rich in solar and wind resources – the Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and Western Cape – have run out of grid capacity, according to Eskom’s Generation Connection Capacity Assessment: 2025.

Thanks to years of loadshedding, private businesses and residents invested in rooftop solar and other energy alternatives, to compensate for the unreliable electricity supply.

By February 2025, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) had a list of registrations for private energy projects with a total installed capacity of 11,857MW – most of it solar. Nersa doesn’t provide information about whether these projects are operational.

It means that private companies have registered through Nersa more alternative energy capacity than the 10,195MW procured through the government’s REIPPP programme.

While the the Northern Cape and Eastern Cape are rich in solar and wind energy potential and are the site of many of the earlier REIPPPP projects, there’s been a big drop in registrations of both private and government projects because of the shortage of grid capacity. The bigger energy projects are now registered for Limpopo and the Free State, where there is space on the grid.

In the most recent REIPPP programme bid window, the successful bids were projects in the Free State, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West.

Eskom estimates that there is 6,178MW of private rooftop solar installed in South Africa. It’s almost as much as Eskom’s installed renewable capacity for 2025, according to the latest status report from Eskom’s National Transmission Company.

Rooftop solar systems, which aren’t connected to grid, are playing a part. They’re alleviating pressure on the national grid, said Eskom spokesperson Daphne Mokwena.

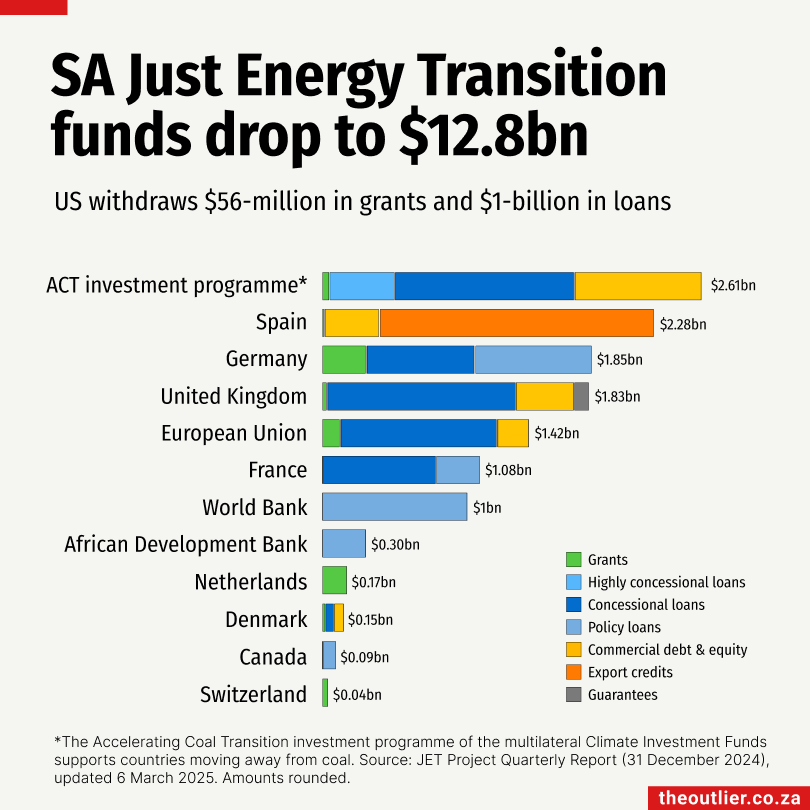

Billion-dollar blow

The United States has withdrawn all the funding it pledged towards the Just Energy Transition (JET), which amounts to more than $1-billion. The US has withdrawn from the International Partners Group, formed in 2021 with France, Germany, the UK, and the EU, to support South Africa’s efforts to decarbonise its economy. Even before this week’s announcement by the presidency, the US had already reduced the grant portion of it’s funding from $63-million to $56-million. The remainder of the funds were in the form of commercial debt and equity.