📝 By Gemma Ritchie and Laura Grant

The finance minister, Enoch Godongwana, managed to present his budget speech this week, and VAT – the sticking point that caused it to be postponed for three weeks – was indeed increased, but by less than the 2% he’d wanted.

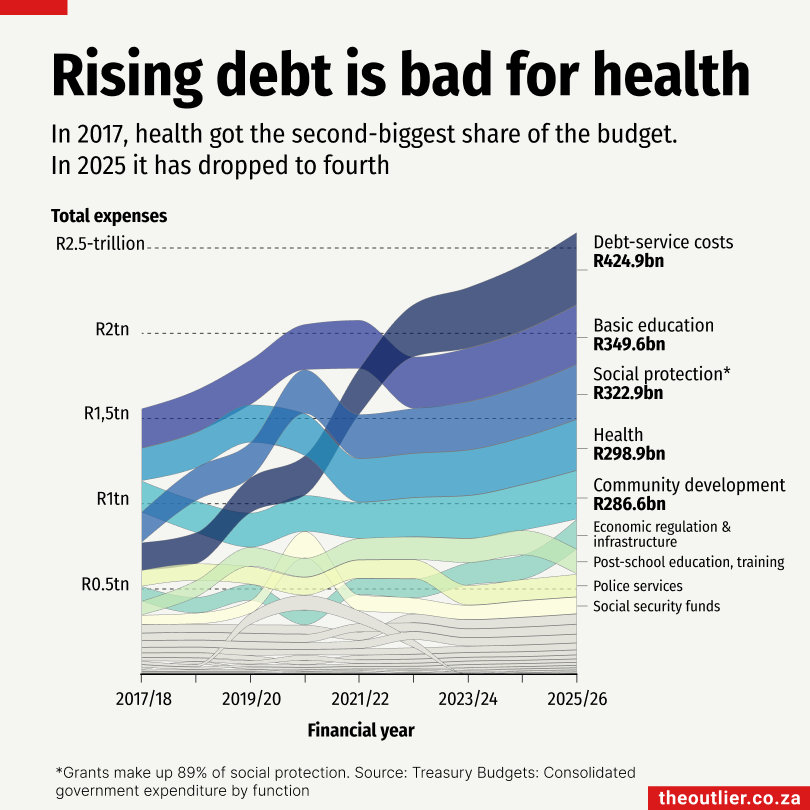

The biggest chunk of the budget is going towards servicing debt (no surprise there, it’s been that way since the 2022/23 budget). As the minister said, 22 cents of every rand we raise in revenue is spent on servicing debt. ‘It is more than what we spend on health, the police and basic education.’

Basic education gets the second biggest slice of the pie – R75bn less than debt servicing. Then comes social protection, 90% of which is social grants. Fourth is health, which got a 7.8% bump on last year’s allocation, more than basic education (7.6%) and social protection (7.6%), but less than debt servicing (9.1%).

A ‘significant portion’ of the health budget is spent on salaries and wages. Yet in the past year, the public health system lost close to 9,000 health workers, Godongwana said. ‘We did not have the money to retain or replace them even after reprioritising funds budgeted for consumables and medicines.’ This does not bode well for National Health Insurance.

The fifth-biggest slice goes to community development, which includes the ‘equitable share’ for municipalities (38%), public transport (23%) and human settlements (15%). The remaining 25% is for municipal infrastructure grants, water and sanitation services and electrification programmes.

Service delivery is deteriorating and funds have to be found. This is why, the minister says VAT has to be increased.

The half-a-percentage-point for two years compromise

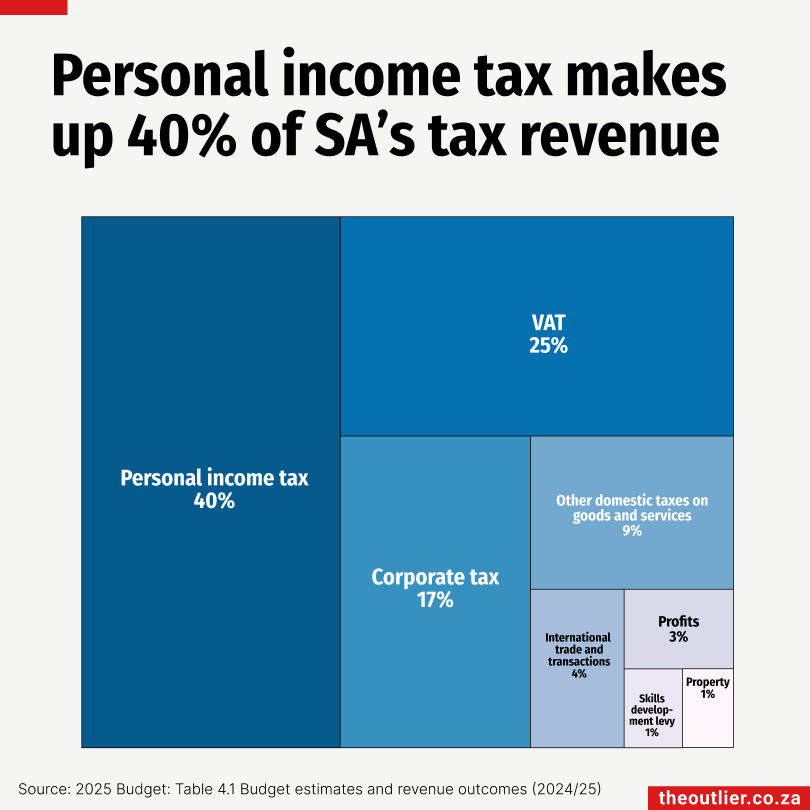

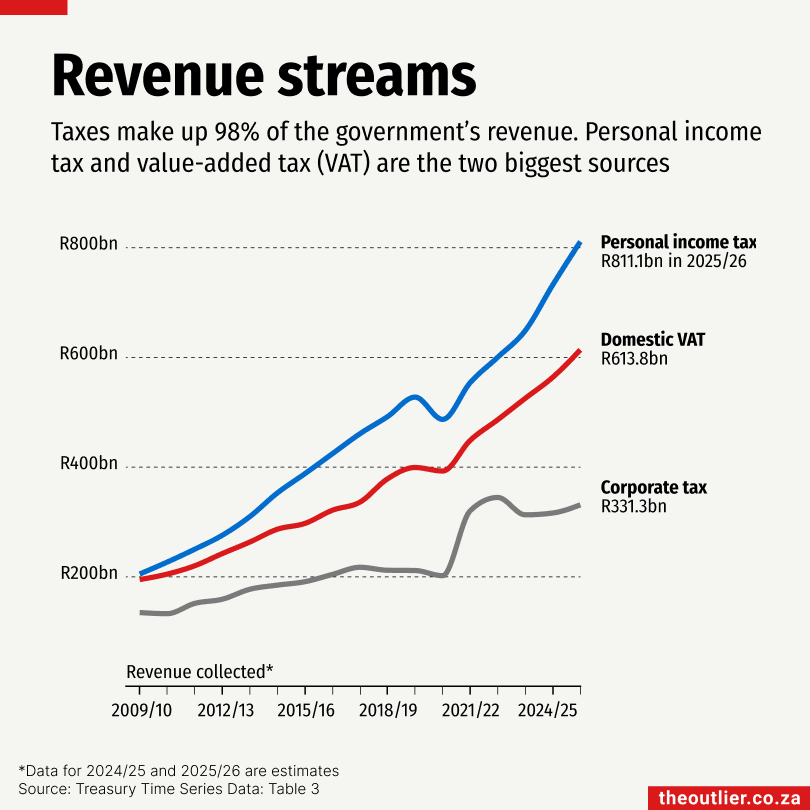

Ninety-eight percent of the government’s revenue is from taxes. VAT contributes a quarter of that tax revenue. But it’s very controversial because it’s seen as a tax on the poor.

‘Dropping the proposed VAT-rate increase from 2% to 0,5% still hurts people and still hurts the economy. Increasing VAT will run through the economy and make every good and service more expensive,’ says Mervyn Abrahams of the Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group, which monitors household expenses of low-income families.

The finance minister seems to believe he didn’t have much choice.‘We thoroughly examined alternatives to raising the VAT rate … Increasing corporate or personal income tax rates would generate less revenue, while potentially harming investment, job creation and economic growth,’he said.

Corporate tax collections have dropped a bit over the past few years. Falling profits and ‘a trading environment worsened by the logistics constraints and rising electricity costs’ are to blame, said Godongwana. So, increasing corporate tax on already stressed companies isn’t an option.

The largest portion of the government’s tax revenue already comes from personal income tax (40%), so why not increase that?

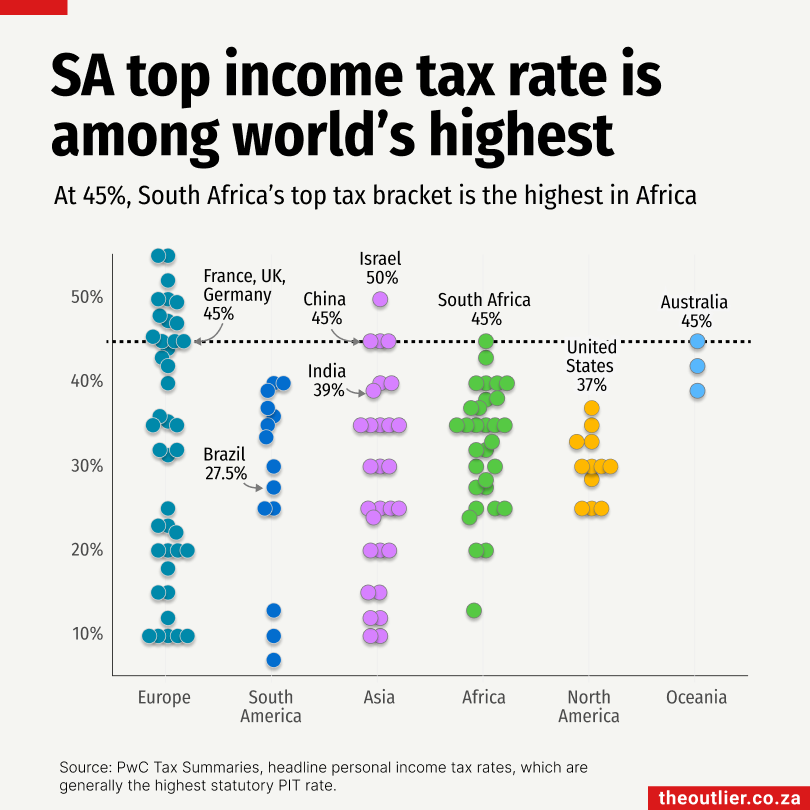

‘Our top personal income tax rate and our personal income tax collections as a percentage of GDP are far higher than those of most developing countries. Increasing it is therefore not feasible,’ said Godongwana.

PWC has a list of the top income tax brackets of 132 countries. South Africa’s, which is 45%, is among the top-10 highest in the world.

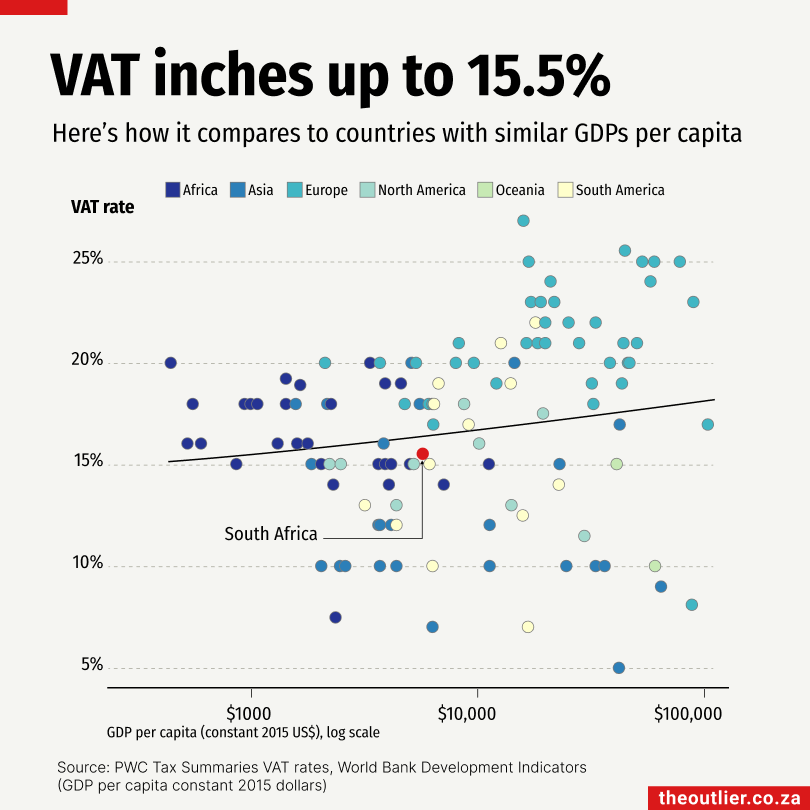

South Africa’s VAT rate, on the other hand, is not particularly high compared with other countries with economies of a similar size. The chart below shows South Africa at 15.5%.

The “who’s paying the taxes?” problem

The 45% tax bracket was introduced in the 2017/18 financial year for individuals with an income of R1.5-million or more. That has increased to incomes of R1.8-million or more.

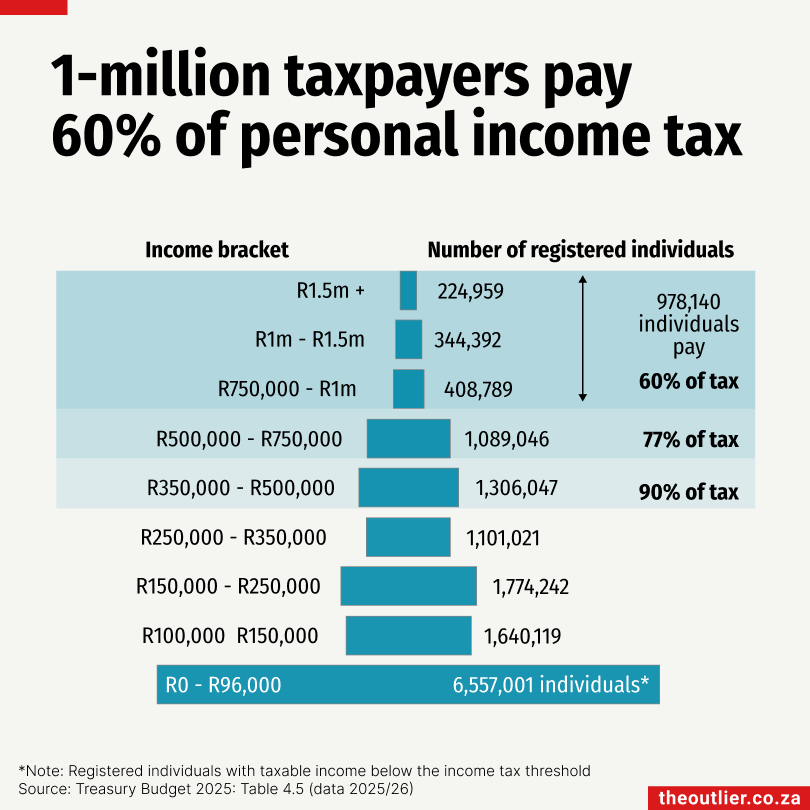

The National Treasury breaks down the registered tax payers into nine income categories (see chart below). In 2017/18, there were 103,353 registered taxpayers in the top income category of R1.5-million and above. In eight years this number has more than doubled to 224,959, but it’s a tiny portion (1.6%) of the country’s 14.45-million registered taxpayers.

Only about 7-million of the registered taxpayers have enough income to be eligible to pay tax and fewer than 1-million pay 60% of the the personal income tax. Those are the people in the top three income categories, which start at R750 000.

In the 2017/18 financial year, people in the top three income groups contributed 50% of personal income tax revenue. Their share has increased to 60% of revenue.

The number of people in the top three income brackets has doubled over the past eight years, although it’s still only 978,140. The number of people eligible to pay tax has remained relatively flat at around 7-million.

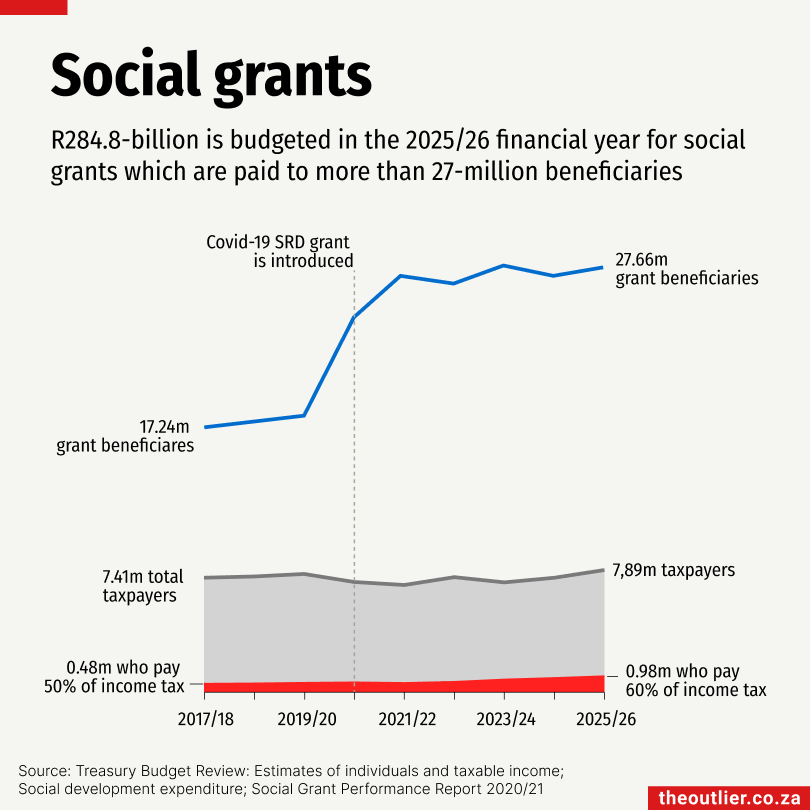

Over the same period, the number of grant beneficiaries has grown by 60%, driven largely by the Covid-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant which was introduced during the pandemic. At the end of December 2024, 26-million people received grants, half (13.5-million) were to support for children, such as child support and foster care grants, 4.1-million were for pensioners and 6.9-million were SRD Covid grants.

There are now about four grant beneficiaries for every taxpayer.

The finance minister says the SRD Covid grant will continue because it serves as ‘a basis for the introduction of a sustainable form of income support for unemployed people.’