The week that was in charts.

🚨 Alcohol-fuelled

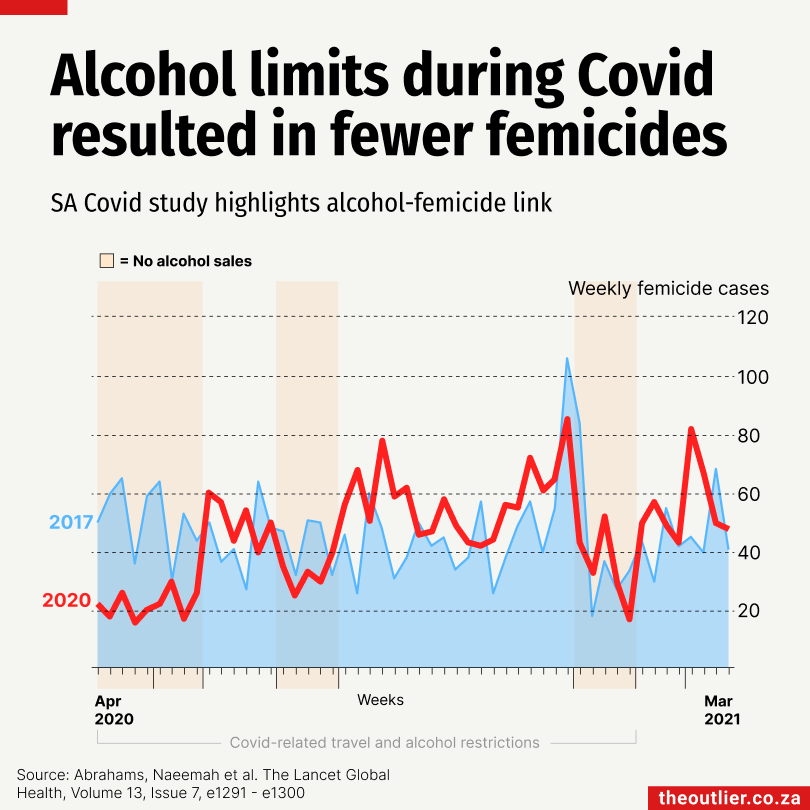

Alcohol use has previously been linked to an increase in femicide but research on this in lower- and middle-income countries has been relatively scarce. Now a new study using data from South Africa during the Covid-19 lockdowns offers new insight.

The study found that during periods when alcohol sales were completely banned, the number of women killed, by both intimate partners and non-partners, dropped by 63% compared to periods with no restrictions.

Researchers compared national data from 2017 with the first year of the pandemic (2020–21), during which varying lockdown restrictions, including bans on alcohol, were enforced.

The pattern of fewer reported femicide cases was most obvious in the early stages of the Covid restrictions, between April and May 2020.

From the report: “The findings support alcohol use as a significant risk factor for femicide and underline the need for alcohol harm reduction policies as part of gender-based violence prevention strategies. Despite public fears early in the pandemic that lockdowns might worsen violence against women, this data shows that limiting alcohol availability may reduce the most extreme form of such violence.”

🏫 New schools needed

Gauteng needs about 200 new schools to accommodate the fast-growing number of schoolchildren, the province’s education department head, Matome Chiloane, estimates. It’s looking to the private sector to help fund this monumental building project.

This year it reportedly received money from the National Treasury to build 18 schools, but that’s clearly not enough to meet even the immediate need for new schools identified by Gauteng’s education department.

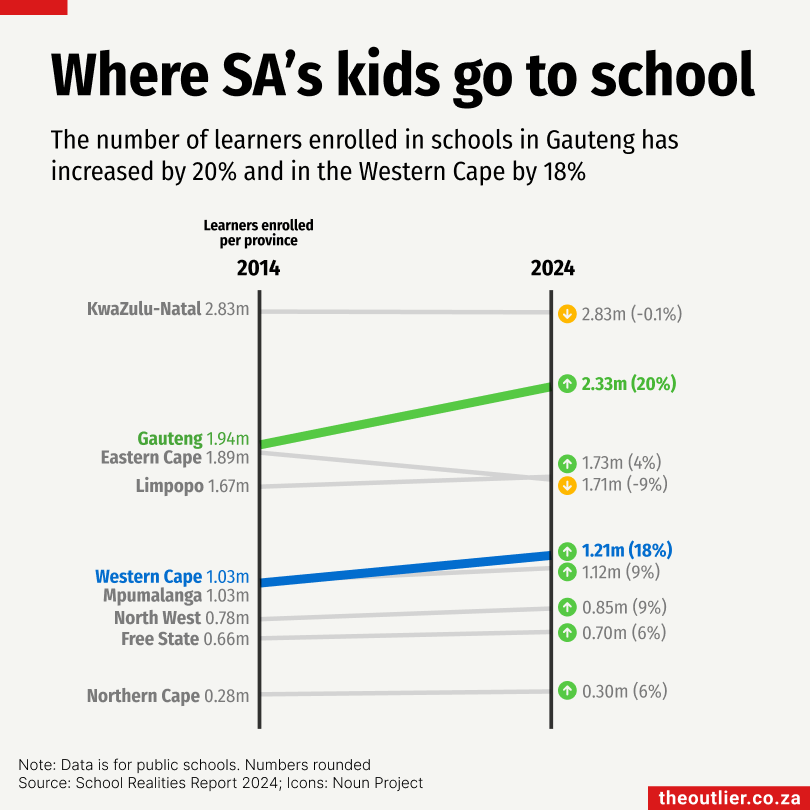

The number of learners enrolled in schools in Gauteng has increased by 20% in 10 years. In 2024 there were 2.3-million of them in the province’s public primary and high schools, up from 1.9-million in 2014.

The Western Cape is the only other province that has seen such a rapid rise in learner numbers.

The increase in schoolchildren in those two provinces is not news to any of us. What is interesting though is the response of the provinces in terms of building new schools to accommodate them.

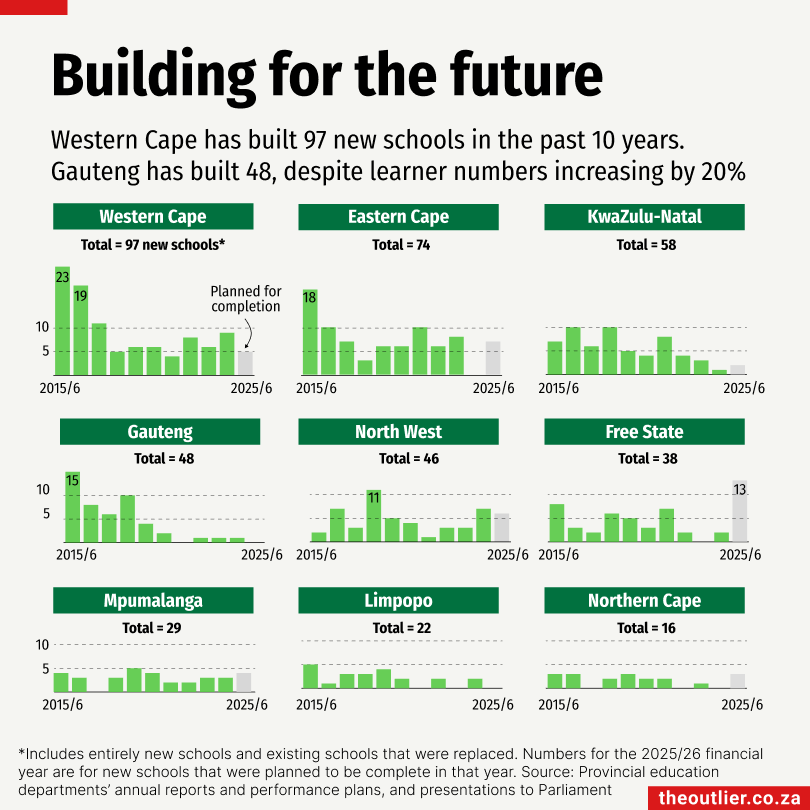

Gauteng built 48 schools in the 10 years between 2015 and 2025, according to information published in the provincial education department’s annual reports from 2015/16 and 2023/24, as well as performance plans and presentations to parliament. This information is not easily accessible, so we had to dig around.

Some of these schools are not technically new because mixed in with new school builds are schools that have been ‘rebuilt’ or replaced because the original buildings were made of unsafe materials like asbestos, for example.

Interestingly, Gauteng has not built any new schools in the past five years, only replacement schools have been completed, according to a presentation to the National Council of Provinces in March 2025.

The last building ‘boom’ in the province was in the 2011/12 financial year when 28 schools were completed and opened. Fifteen schools were finished in the 2015/16 financial year and new builds have tapered off since then.

In comparison, the Western Cape’s response to its learner influx has been much better. That province has built or refurbished 97 schools, with another five planned for completion in the 2025/26 financial year.

In fact, three provinces have built more schools than Gauteng in the past 10 years. Even the Eastern Cape has built (or refurbished) more schools, completing 74 by 2024. This is despite the number of learners actually decreasing by 176,000 over 10 years.

The Eastern Cape is interesting because it has closed far more schools than it has built. It’s part of a ‘rationalisation plan’, which aims to shut down small, often under-resourced rural schools and redirect resources towards urban areas, like Buffalo City and Nelson Mandela Bay, where schools are overcrowded.

Keeping up

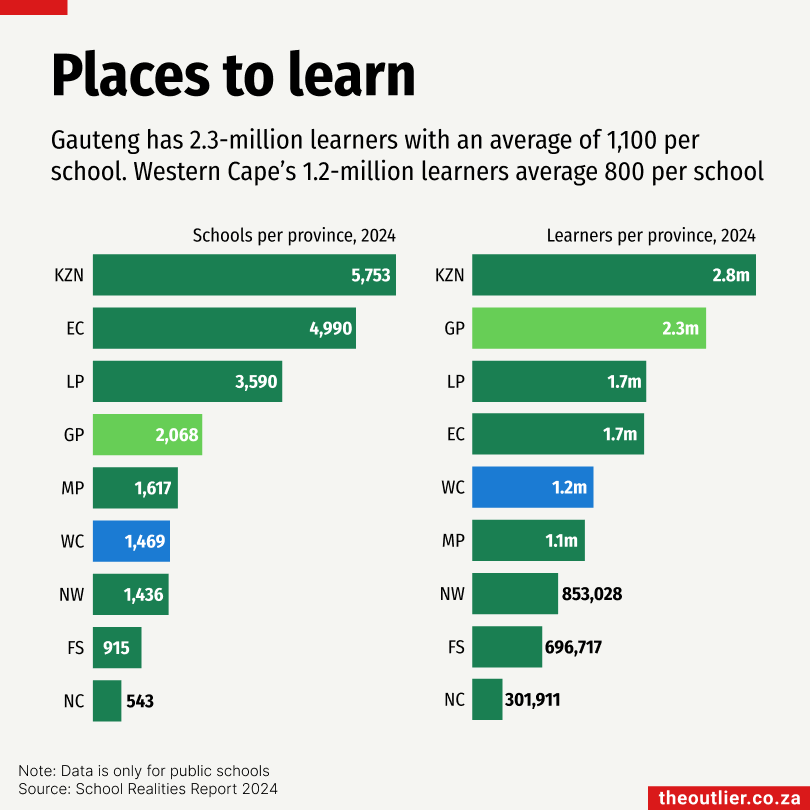

Despite having the second-highest number of learners enrolled in its public schools – only KwaZulu-Natal has more – Gauteng does not have the second-highest number of public schools. It ranks fourth, with 2,068 schools – behind KwaZulu-Natal (5,753), the Eastern Cape (4,990), and Limpopo (3,590).

Those three provinces tend to have many small rural schools.

The Schools Act classifies the types of schools in South Africa from ‘micro primary schools’ with fewer than 135 learners to ‘mega primary schools’ with more than 930 learners. Micro high schools have fewer than 200 learners and mega ones have more than 1,000.

Averaging the number of learners per school by province shows this pattern, Gauteng has an average of 1,127 learners per school, followed by the Western Cape at 823 learners. In the rural provinces, the average is much lower. Eastern Cape has 343 learners per school, KwaZulu-Natal has 492 and Limpopo has 482. Gauteng and the Western Cape have fewer, but much bigger, schools.

The number of learners enrolled in Gauteng’s schools has increased by just over 385,000 over 10 years and the number of new schools built is 48, that means each new school would have to accommodate an average of 8,000 of those new learners. Those would be superduper-mega schools.

If Gauteng had built one new school for every 1,000 new learners over the past decade, the province would have built at least 380 schools.

The picture is different in the Western Cape: there the number of learners enrolled in public schools has increased by around 182,000 and it has built 97 new schools, which is an average of 1,870 learners per new school. That number looks a bit more manageable.

Gauteng has no new schools due to be completed in the 2025/26 financial year, according to a presentation to parliament earlier this year. It needs to get a move on.

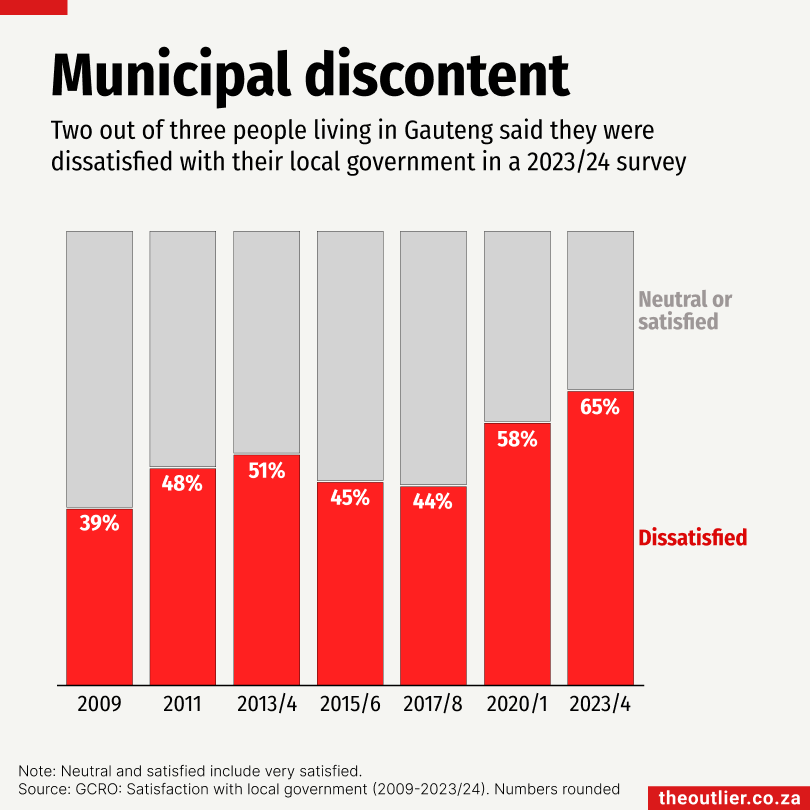

😡 Municipal discontent

Public satisfaction with local government is collapsing in Gauteng.

Nearly two out of three people who were part of the Gauteng City-Region Observatory’s (GCRO) latest Quality of Life survey said they were either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the province’s local governments (aka municipalities).

No surprise there, given the string of service delivery failures. From potholed roads and dry taps to power outages caused by ageing infrastructure, residents have also had to endure a cholera outbreak in Hammanskraal, Tshwane, a deadly fire in the Johannesburg CBD at 80 Albert Street and a gas explosion on Lillian Ngoyi Street, all in 2023.

Public dissatisfaction is unlikely to ease anytime soon. Both Tshwane and Emfuleni have been in concerning financial positions for three and four consecutive years, respectively.

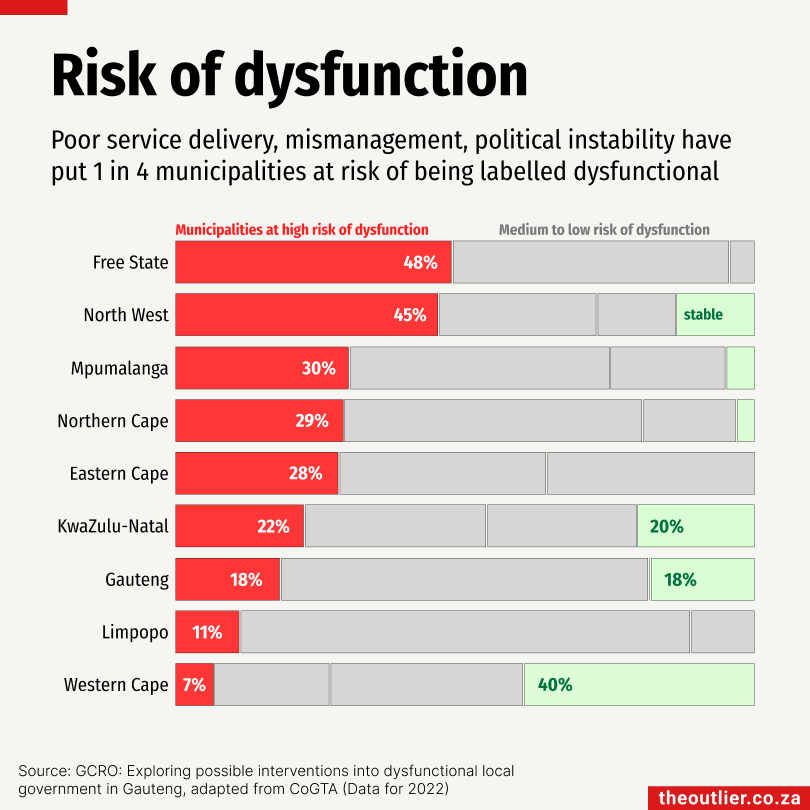

Municipalities with ongoing financial management issues, risk being classified as dysfunctional.

In a report entitled ‘Exploring possible interventions into dysfunctional local government in Gauteng’, Dr Claire Franklyn writing for the Gauteng City-Region Observatory, uses statistics from the Department of Cooperative Government and Traditional Affairs showing just how many municipalities are classified as being at risk of dysfunction.

The chart below uses 2022 data to show the proportion of local municipalities in each province considered at risk as well as the sadly tiny proportion classified as ‘stable’. The Western Cape is the star performer here.

🤔 Chart quiz

Can you complete this chart?

How many international tourists arrived in Cape Town in December last year?

Which of the dotted lines is the correct finish to this line?