In Southern Africa, maize is a staple food for millions of people eaten as pap, sadza and nshima. There has, however, been a devastating decline in production across the region because of dry and hot weather caused by El Niño weather patterns.

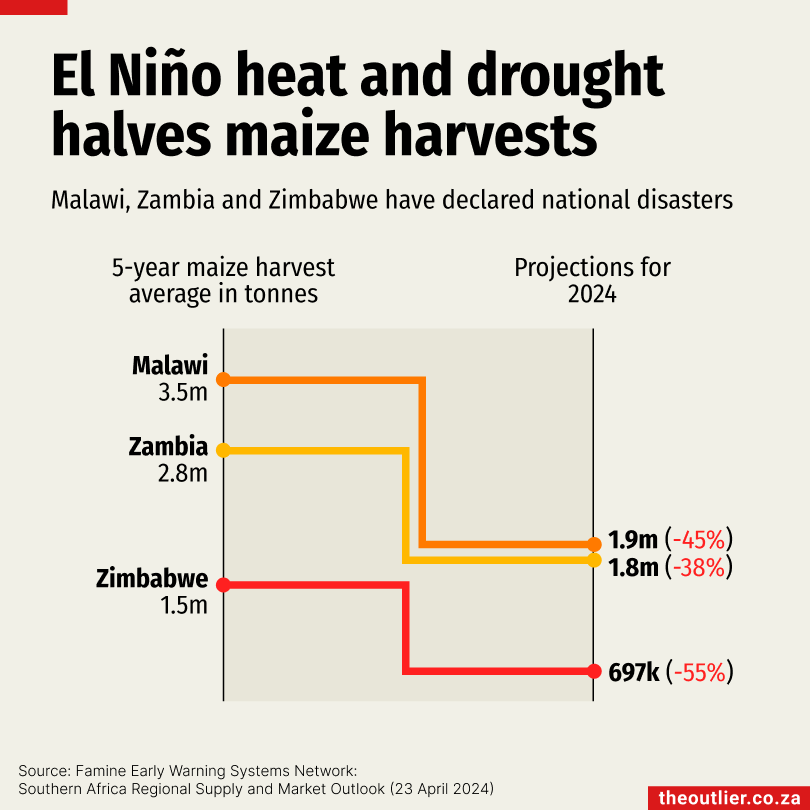

Three countries declared a state of disaster earlier this year: Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Zambia is experiencing its driest agricultural season in more than 40 years, according to a report by the United Nations. The country lost almost half of the maize it planted, close to 1-million tonnes, describing it as ‘total crop failure’.

What is El Niño?

El Niño is a weather phenomenon that takes place when the ocean’s surface temperature increases, causing a warmer atmosphere. El Niño occurs every two to seven years, but it can last for months. From November to April, it typically brings heatwaves, below-average rainfall and drought to southern Africa, leading to poor crop yields and water scarcity.

This shortage has caused widespread hunger and malnutrition, particularly among children and other vulnerable people.

The importance of maize

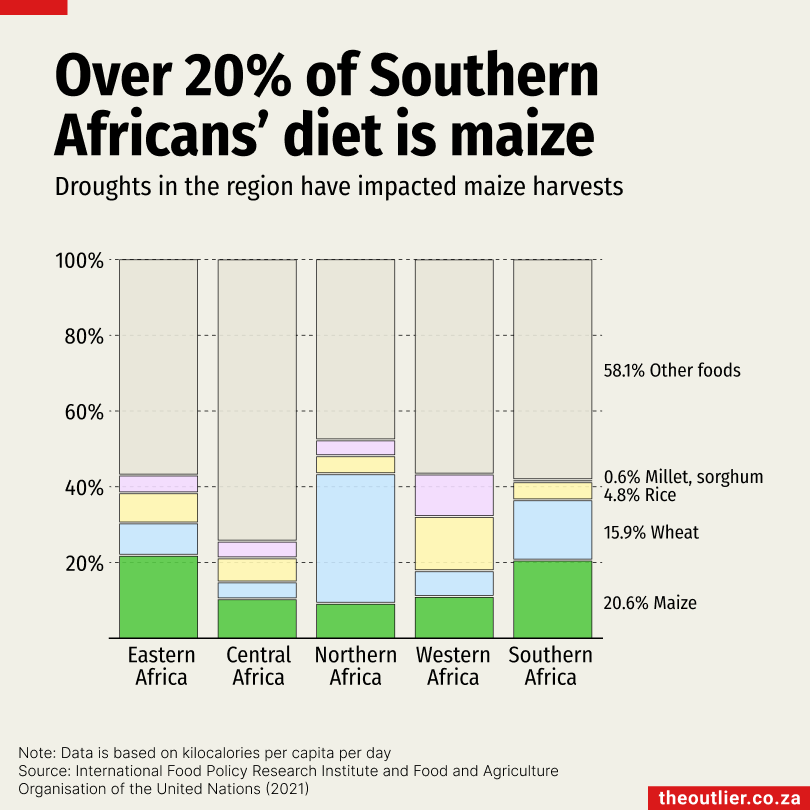

Maize is critical to food security in Southern Africa, making up more than 20% of the average person’s daily diet (in kilocalories consumed). It’s the second-highest proportion on the continent, according to data from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

More than 6.55-million people in Zambia, many of them children and women, now need humanitarian assistance, the UN says.

In Malawi, 4.2-million people are likely to be experiencing ‘high levels of acute food insecurity’ by September, the International Food Policy Research Institute reports. The country is still recovering from last year’s El Niño-driven flooding and drought, and food insecurity outcomes have been exacerbated by reduced incomes and high food prices.

Zimbabwe’s looming famine

After declaring a state of disaster in April, Zimbabwe expects to produce 55% less maize than usual in 2024. About half the population is likely to go hungry as a result, the UN says.

Zimbabwe will need to import 1-million tonnes of maize to make up the shortfall from its harvest, says Wandile Sihlobo, chief economist at the Agricultural Business Chamber of SA. All of its imported maize will come from South Africa, which will ‘most likely only have 1.4-million tonnes to export because of its poor harvest’.

In the first two months of 2024, South Africa exported 224,130 tonnes of maize to Zimbabwe, which is almost half its regional export total of 463,000 tonnes.

Zambia is unlikely to import maize from South Africa as it prohibits the cultivation and import of genetically modified maize (85% of South African maize is genetically modified). The country will have to put its faith in Mexico and Tanzania for GMO-free maize supplies, Sihlobo says.

Better harvests

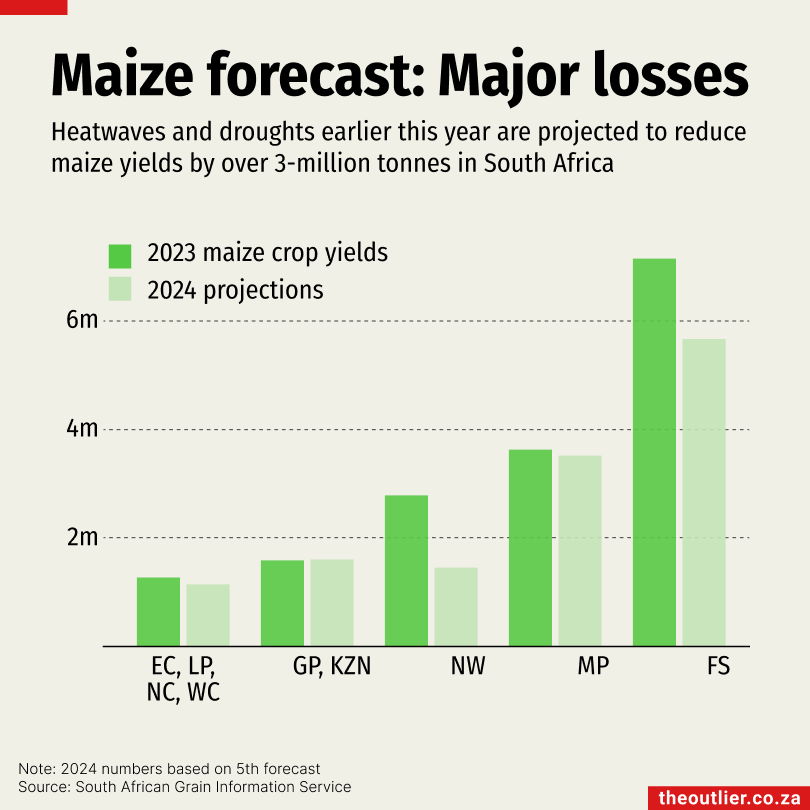

While still heavily impacted by the drier summer months, South Africa has faired better than its neighbours because of the ‘differences in farming practices, better timing of the planting window, and the improved seed cultivars’, says Sihlobo.

In North West, however, maize harvests are projected to drop by almost half from 2023’s numbers. Other significant drops are expected in Limpopo (35%) and Free State (21%), the main maize-producing province.

Rocketing prices

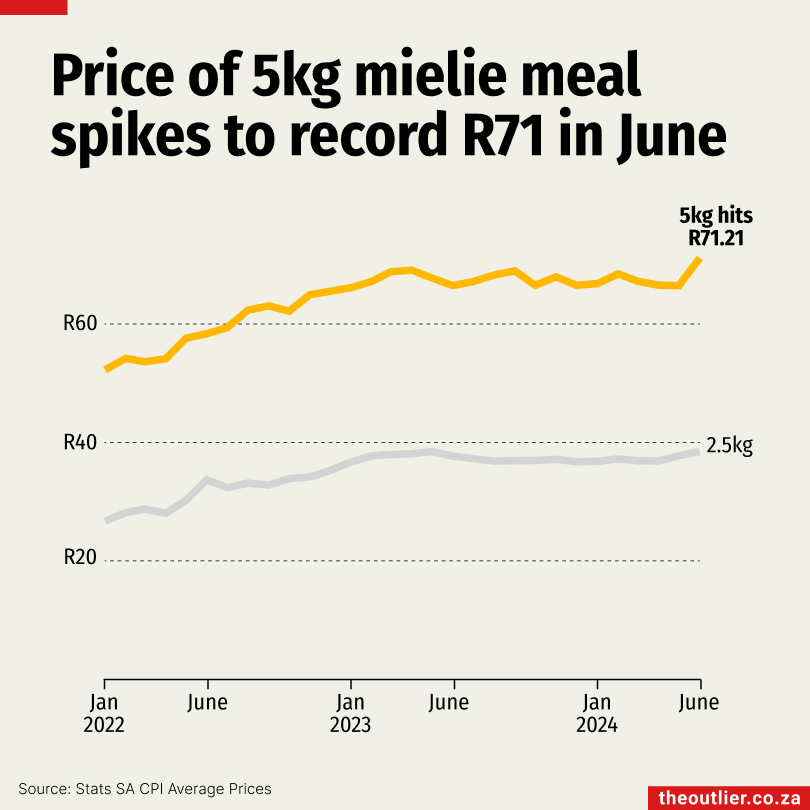

Shortages are driving up the price of mielie meal. The price of a 2.5kg bag in South Africa has increased by R12 since January 2022, which is as far back as Statistics SA’s data goes. That’s a 44% increase in just two-and-a-half years. Other staple foods, such as white bread and tinned fish, increased by half as much over the same time period.

A 5kg bag of maize meal is now the most expensive it has ever been at R71.21.